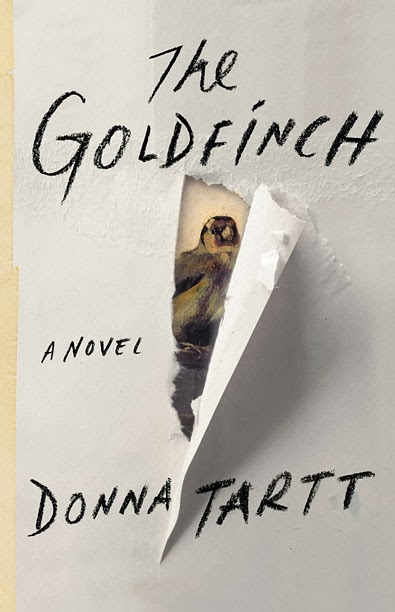

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

The Goldfinch is Donna Tartt's long-awaited third novel, and weighs in at close to 800 pages. A rambling narrative full of tangents and episodic subplots, it's reminiscent of a modern version of a hefty Victorian novel, almost Dickensian: a tale of the changing fortunes of an orphaned boy and the impact upon him of his own poor decisions and his relationships with those he meets on his journey to adulthood. There's an unrequited love for a tragic, damaged childhood sweetheart, there are long periods of sickness and fever, there's a wicked stepmother, kindly benefactors, sinister criminals, long and treacherous journeys, threats of being 'sent away' to school, an unwise engagement. One could certainly never accuse The Goldfinch of being a novel that lacks scope.

It opens with 13-year-old Theo Decker, suspended from school for a minor misdemeanour, visiting a New York museum with his art-loving mother. During the visit, a horrific incident rips the museum, and Theo's life, apart. As he escapes the aftermath, he takes with him one of the museum's most famous exhibits: The Goldfinch, a priceless painting by Carel Fabritius.

It opens with 13-year-old Theo Decker, suspended from school for a minor misdemeanour, visiting a New York museum with his art-loving mother. During the visit, a horrific incident rips the museum, and Theo's life, apart. As he escapes the aftermath, he takes with him one of the museum's most famous exhibits: The Goldfinch, a priceless painting by Carel Fabritius.

It opens with 13-year-old Theo Decker, suspended from school for a minor misdemeanour, visiting a New York museum with his art-loving mother. During the visit, a horrific incident rips the museum, and Theo's life, apart. As he escapes the aftermath, he takes with him one of the museum's most famous exhibits: The Goldfinch, a priceless painting by Carel Fabritius.

It opens with 13-year-old Theo Decker, suspended from school for a minor misdemeanour, visiting a New York museum with his art-loving mother. During the visit, a horrific incident rips the museum, and Theo's life, apart. As he escapes the aftermath, he takes with him one of the museum's most famous exhibits: The Goldfinch, a priceless painting by Carel Fabritius.

Estranged from his absent father and terrified of being sent to live with possibly abusive grandparents that he has barely met, Theo is left at the mercy of the adults around him, very few of whom have his best interests at heart. As Theo grieves for his mother and searches for some sort of purpose in a life that seems empty and directionless, the stolen painting simultaneously becomes a comfort and a burden, a talismanic connection to his final moments with his mother and a lone reminder that there are still shreds of beauty in a hostile world, and yet at the same time a symbol of Theo's guilt, fear and self-loathing.

Far from concise, The Goldfinch is heavy on description and detail, with each stage in Theo's life - his stay with the wealthy but brittle Barbour family, his relationship with his estranged father in Las Vegas, his attempt to turn his life around in New York - the subject of long digressions. And yet each is so perfectly realised, so vividly described and full of colour, that not once did I find myself bored.

Perhaps the most rambling section deals with Theo's friendship with Boris, a mercurial loose cannon of a character somewhat reminiscent of a teenage Eugene Hutz. Like Fabritius' Goldfinch, Boris is both a blessing and a curse. Boris' friendship is a burning spark that reignites bereaved, displaced Theo's lust for life and provides an anchor of affection, even love, that Theo has lacked since his mother's death - yet at the same time, it's Boris who introduces 14-year-old Theo to alcohol, to shoplifting, to drugs. Another character later likens Boris to the Artful Dodger, and this comparison is largely accurate - Boris is not the baby-faced, cheeky urchin of the musical Oliver! but is certainly not unlike the manipulative, cunning, eerily adult child pickpocket of Dickens' original novel, who takes Oliver under his wing and saves him from starvation on the street, but at the same time draws him into a dangerous adult world of violence and crime.

Much of The Goldfinch deals with these sorts of contradictions, with the duality of relationships, objects, people and places. Its emotional and philosophical range is as ambitious as its narrative one, and I found myself caught up in, and gripped by, this novel. It's very difficult to like Theo Decker at times: plagued with survivor's guilt, he's self-destructive, easily led, suffocated by his own regrets and, like the father he despises, irresistibly drawn to risk-taking and deception. Barely a chapter passed when I didn't want to reach into the pages and shake him by the shoulders at best, stage a full-scale intervention at worst. And yet I never stopped caring about him or, oddly, the painting of the title, which assumes a significance far beyond that of a work of art.

The Goldfinch's one weakness for me is its final chapter, in which far too much is spelled out by the narrator, which, while beautifully articulated, would have been better left implied. I had already drawn my own conclusions about what Theo might have learnt during the course of the narrative, and I didn't find it especially illuminating to have it summarised for me in this way. A few pages that drag are hardly a problem in a 771-page novel, but it's a pity that those pages were the last 10 or 20 pages in the book.

Comments

Post a Comment