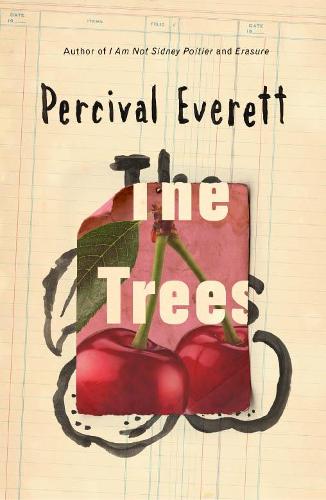

The Trees by Percival Everett

The setting for The Trees is Money, which Everett tells us is a town in the Mississippi Delta named 'in that persistent Southern tradition of irony' and 'living proof that inbreeding does not lead to extinction'. Everett's description of the poor, shabby and insular community is therefore far from flattering, but Money is in fact a real place, and one that is known for one thing and one thing only: the horrific and unpunished murder in 1955 of a 14-year-old black child called Emmet Till, who was accused of whistling at a white woman outside a grocery store. Till's mother insisted on an open coffin at her son's funeral, despite the extent of his injuries and the ravages of the water his body was found in: she wanted people to see the full horror of what the white lynch mob had done to him.

That, then, is the context for The Trees. It begins with the death of Wheat Bryant, whose ancient grandmother, Granny C, occasionally mutters vaguely remorseful remarks for an incident in her past involving a young black boy.

Like most of the white characters, the Bryants are deliberately and hilariously grotesque caricatures: stupid, dysfunctional, angry, lazy racist rednecks. Wheat's wife is known to everyone (including her own neglected children) as Hot Mama Yeller after the call sign she uses to chat to truckers over CB radio; his brother is called Junior Junior. It's hard, then, to feel any sense of surprise that someone might have wanted to murder Wheat - I could happily have murdered him myself. The real mystery, and one that becomes increasingly unsettling as the story unfolds and more deaths occur, is that there next to Wheat's corpse is a second body, which is that of a shockingly mutilated young black man. Who is he? What has happened to him? And most disturbingly of all, how and why does his corpse keep disappearing from the mortuary and turning up at the scenes of further murders?

Attempting to make some sort of sense of what's happening in Money are two black agents from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, Ed and Jim, who form a drily witty comedy double act as they patiently interview the racist locals and law enforcers. Also key to the plot are Damon Thruff, an academic who has written a book on the history of racist violence; Gertrude, who goes by the name of Dixie in her job at Money's terrible diner and although mixed race apparently 'passes' as white; and Gertrude's elderly grandmother Mama Z, a mysterious 105-year-old matriarch who has spent most of her life cataloguing lynchings as an expression of her outrage. She has nothing but disdain for the scholarly approach of Thruff's well-meaning book.

As Ed and Jim try to solve the mystery, it becomes clear that this is something bigger than Money, and bigger than Mississippi. Similar deaths start to spread through other states. In California, Ed and Jim are unsettled to find two Asian-American detectives investigating a spate of murders where the accompanying recurring cadaver is that of a Chinese man. If this doesn't ring any bells with you, you might want to Google 'Los Angeles 1871'.

I don't think I've ever read a book that is simultaneously so funny and so powerful. I laughed out loud several times, and yet there could be no more serious and enraging subject than this. When I wasn't laughing, I was furious. As the story develops, we realise that this isn't a book about solving a mystery at all: if there's anything to be investigated, it's the decades of shocking injustice that saw hundreds of black and Asian Americans murdered by their white neighbours with almost total impunity - and the general lack of attention we give these historic crimes today. You shouldn't expect much in the way of resolution from The Trees - if anything, the sense of simmering anger and rising panic merely increases. This is not the end of something, but the start.

Everett takes a full chapter of The Trees to list all the recorded victims of lynchings in the United States, and you do those victims a disservice if you don't take the time to read each and every name.

Comments

Post a Comment