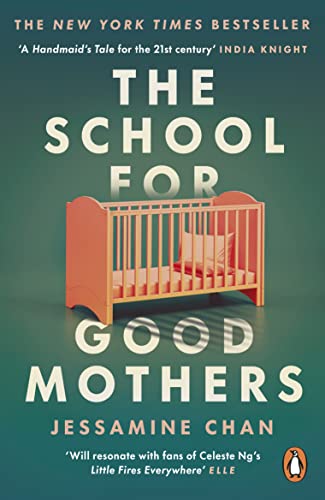

The School For Good Mothers by Jessamine Chan

I don't have any children, but if there's one thing I've noticed about social media, it's that people really, really like to judge a mother. Not fathers, obviously. Just mothers. No celebrity or influencer is safe from people chipping into their Instagram comments to tell them they're holding their baby wrong or shouldn't be giving their toddler cereal or that their house is insufficiently childproof, and Facebook is full of people moaning that some woman on the bus was looking at her phone instead of chatting to her child. As the great Stacey Solomon would say: HAVE A DAY OFF, SUSAN.

Jessamine Chan's novel The School For Good Mothers takes the incessant judgement of mothers to the next level and combines it with increasingly right-wing attitudes to women and their bodies in America to create a present-day dystopian tale that chilled me, even as a non-parent, to the bone.

Frida Liu is a Chinese-American woman living in Philadelphia with her toddler Harriet. Harriet's father, Gust, left Frida for his younger, whiter, wellness-obsessed mistress when Harriet was three months old, and while the two of them co-parent Harriet with a 50-50 arrangement, Gust has his new partner's help with childcare while Frida has to manage alone.

One day, struggling with depression and after days and sleepless nights of nursing a needy, grumpy Harriet through a childhood bug, Frida realises she's forgotten some important paperwork that she needs from her office. Terrified of losing her job and barely able to think from lack of sleep, she puts Harriet into her baby walker to keep her safe and walks out of the apartment alone to go and collect the work she needs, leaving Harriet behind. This is Frida's 'very bad day', and her split-second decision made in a state of exhaustion and panic has shocking consequences when her neighbours call the police.

All of this, of course, is something that could easily happen today, and nobody would argue that it's unfair for a neighbour to alert the authorities if a baby is screaming alone in an apartment. Frida herself is fully aware that she's had a terrible lapse in judgement and that her mistake is never to be repeated, and we might expect social services to make some kind of assessment as a result. But what happens next is what takes the story into dystopian territory: in order to stand a chance of getting her daughter back, Frida must spend a year at a secure facility - to all intents and purposes, a prison - learning to be a 'good mother'.

There are certainly echoes of The Handmaid's Tale in this book, and strong sense of societal misogyny that has crept up slowly on America until it's reached a shocking point of no return. Although there is an equivalent parenting school for fathers, there are far fewer inmates and they are treated very differently and judged on less stringent criteria. The mothers are expected to wear a one-size prison uniform and essentially have all sense of their own self replaced with that of someone who is a mother, and only a mother. They're expected to have well-behaved children, but are also expected not to shout or say 'no'. They must show affection, but not too much affection, or the wrong kind of affection. They must learn different types of hug for different situations. They must never take their eyes off their children, even for a second. And most importantly, they must never, ever forget that they are bad mothers. They're taught to hate themselves, to feel constantly guilty - primarily by their teachers, most of whom are other women and at least some of whom aren't themselves parents. The mothers at the school will never be good enough, and they will be made to remember that.

The notion of a 'bad mother', it seems, encompasses all manner of failings. Frida left her child alone in her apartment for an hour or so; other mothers she meets have allowed a teenage relative to mind their baby for an afternoon, or left their child in the car while they go to a job interview, or simply let them play outside without watching them the whole time. And yet there are also mothers at the facility who have burnt their children with cigarettes, hit them or locked them up in damp cellars to go out. One mother refuses to let her 17-year-old son fasten his own shoes or shave without her help; he seeks outside help when she announces she'll be moving with him when he goes to college. There's no difference, far as the school is concerned, between mothers like this and a mother whose child bumps their head when her back is turned. They are all narcissists. They are all failures. They are all bad mothers.

I don't have any children, but the pain of Frida's separation from Harriet felt almost viscerally real, and there were parts that I found genuinely difficult to read, all the more so because it's clear that Harriet is as traumatised as Frida by their sudden and prolonged parting. While separated from their own children, they are allocated hyper-realistic AI-driven dolls to care for, dolls which to all intents and purposes have the physical and emotional feelings of human children. At first, this feels like true uncanny valley territory, and it certainly is sinister, but there is also a terrible underlying sadness about the dolls, who in order for the mothers to learn to comfort them, have to be repeatedly hurt and distressed. That too was something I found truly harrowing, and the ethical implications of the dolls' treatment are the kind of thing I can imagine explored by Kazuo Ishiguro.

As well as the obvious feminist themes of The School For Good Mothers, Chan also explores some interesting ideas about race and class. When Frida's interactions with her child-doll are deemed insufficiently expressive, what the trainers really mean is that she isn't being American enough; when the psychologist suggests that Frida's own childhood was a damaging one, the obvious subtext is that her (perfectly kind, loving and effective) parents, as first-generation Chinese immigrants, should have adopted Western parenting behaviours instead of acting according to their own cultural norms. Working class mothers at the school are often there because of situations arising from, say, being unable to find an affordable babysitter.

The School For Good Mothers is far from an uplifting read. The whole concept is chilling and executed with frightening plausibility, and the plot itself doesn't move at any great speed - in fact there's an ominous inevitability about it. But none of those things stopped me from wanting to turn the pages, and I couldn't put this book down.

Comments

Post a Comment