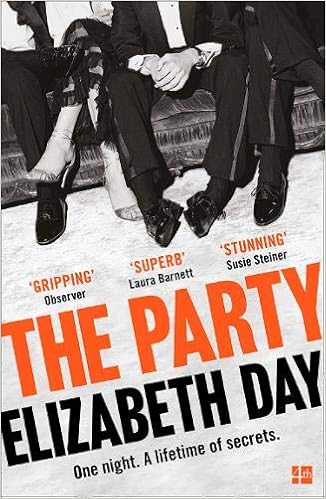

The Party by Elizabeth Day

The Party by Elizabeth Day opens with Martin Gilmour, being interviewed at a police station after an unspecified incident at an impossibly glamorous 40th birthday party held by his super-rich friends, Ben and Serena Fitzmaurice. Just to give you a sense of the sort of party it is, and the sort of people Ben and Serena are: their home is a former monastery, the entertainment at the party is a world-famous boy band and one of the guests is the Prime Minister. As Martin continues to answer questions, the story of the friendship between Martin and Ben, and what happened at Ben's party that led to a police investigation, starts to unfold into a dark satire on class, money and power.

The Party by Elizabeth Day opens with Martin Gilmour, being interviewed at a police station after an unspecified incident at an impossibly glamorous 40th birthday party held by his super-rich friends, Ben and Serena Fitzmaurice. Just to give you a sense of the sort of party it is, and the sort of people Ben and Serena are: their home is a former monastery, the entertainment at the party is a world-famous boy band and one of the guests is the Prime Minister. As Martin continues to answer questions, the story of the friendship between Martin and Ben, and what happened at Ben's party that led to a police investigation, starts to unfold into a dark satire on class, money and power.Martin, it transpires, met Ben at public school, where Ben was a handsome, super-wealthy minor aristocrat with a large inheritance ahead of him and Martin was a bright lower middle-class boy on a full scholarship. From day one, Martin has worked to try to bridge the vast gulf between them in terms of class and background, eventually becoming a successful journalist and critic, and after 25 years or so, the two remain best friends. But there are clues scattered throughout the story - and observations made rather more openly by Martin's wife Lucy - which suggest that there is something not quite right about this friendship. Why are Martin and Lucy staying at a budget hotel for the party, while other friends and family have been accommodated at Ben and Serena's enormous house, for instance?

Martin, it soon becomes clear, has an awful lot of secrets, and he and Ben are tied together by far more than a childhood friendship. Something's got to give - or someone.

This is one of those books in which every character is passively irritating at best or outright unpleasant at worst. Martin's wife Lucy seems to have some sort of moral compass but I don't believe in her relationship with Martin for a moment and her weak, downtrodden willingness to be forever second-best is infuriating rather than endearingly loyal. Everyone else, frankly, wants punching in the face. This isn't necessarily a problem - we shouldn't have to like characters to care about what happens to them - but it does mean there's an odd coldness to the experience of reading this book. It also means that the plot, and the satire, need to work extra hard to compensate - and I'm not sure they really deliver.

The observations about class and money and privilege are entertaining and often funny, particularly when the small details of the characters' lifestyles and behaviours are being described, but the overall points made are far from revelatory - I don't think any of us are exactly unfamiliar with the notion that it's hard for a teenager with a background like Martin's to fit in at public school, or that wealth and privilege come with valuable connections, or that the upper classes are afforded opportunities that others are denied and call their children things like Cosima and Hector.

I get the impression that The Party is aiming to be a sort of cross between Brideshead Revisited and Notes On A Scandal with a touch of Mark Lawson's The Deaths, but although it's a diverting read, it's not entirely satisfactory. There aren't many surprises, and the big reveal about exactly why Martin is being interviewed by the police is a real anticlimax. Finally, as a protagonist, Martin wasn't particularly believable to me, and I'm really very much over stories in which the working- or middle-class character idolises and desperately seeks to imitate wealthier, more privileged classmates or colleagues.

Comments

Post a Comment