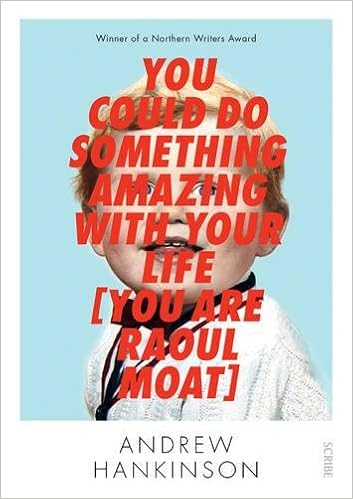

You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life [You Are Raoul Moat] by Andrew Hankinson

Although I review novels, I don't often post on my blog about the non-fiction I read. I'm making an exception for Andrew Hankinson's You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life [You Are Raoul Moat] because, although it's effectively true crime, it reads like a brilliantly written novel.

Although I review novels, I don't often post on my blog about the non-fiction I read. I'm making an exception for Andrew Hankinson's You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life [You Are Raoul Moat] because, although it's effectively true crime, it reads like a brilliantly written novel.The only difference is that this time, we all know how the story ends. Raoul Moat, after hospitalising his former partner Sam (who was also the mother of one of his children), murdering her new boyfriend Chris Brown and permanently blinding police officer David Rathband, shot himself in the head after a week-long manhunt, during which he lived rough in the woods near Rothbury, Northumberland. We watched it all unfold on rolling news channels. And yet this compelling narrative, which addresses Moat throughout as if we, the reader, were seeing the unfolding horror through his eyes, is every bit as gripping as any thriller.

You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life [You Are Raoul Moat], written in the second person, has all the tense, immersive immediacy of a computer game or a choose-you-own-adventure narrative, but without the comfort of having control over the outcome. Hankinson, a journalist, examined Moat's lengthy written and recorded commentaries on his life and state of mind, as well as other source material, which provides a grim insight into Moat's self-pity, his narcissism and his paranoia. In Moat's head, nothing is ever his fault, including the jail sentence for a violent assault on a child (whose identity isn't stated in the book, I assume for legal reasons, but it's not hard to guess what their connection with Moat have been) during which Sam finally left him. The police, he says, are victimising him pulling him over "one hundred and eighty-four times [Northumbria Police recorded you being pulled over fourteen times between 2000 and 2010]."

The use of brackets is a clever and strangely chilling device that Hankinson employs throughout the book not only to clarify factual points but also to highlight Moat's borderline delusional state of mind. "Well, you moved around a bit, up and down the country [you've lived in Fenham all your life, but you told people otherwise, including a psychiatrist and social workers]." These calm, neutral asides are not only effective in reminding us not to be taken in but are also inexplicably unnerving, even ominous - the book's title, I think, is an excellent example of this, as is adding "[a child]" whenever Moat mentions the victim of his assault conviction.

It's testament to Hankinson's skill that he manages to give us a balanced picture of Moat's life and character while addressing us as if we were him. Hankinson doesn't let Moat's tendency to overplay the degree to which he's been wronged - Sam hurt him 'with words' more than he hurt her physically, Moat says, of the woman he beat, throttled, threw downstairs and stamped on and ultimately shot - overshadow the genuine misfortunes he experienced in his life, such as a mentally ill mother, no contact with his father and difficulties in being taken seriously when expressing concerns to various authorities about his own mental instability and self-acknowledged violent tendencies. Towards the end of the book, we learn something about Moat's father that is not only a revelation - it certainly doesn't add up to the account Moat has given - but is also remarkably sad. The account of the police negotiator's conversations with Moat in the hours leading up to his death also gives a revealing insight into his vulnerabilities.

Ultimately, though, Hankinson never asks us to make excuses for Moat, and this is a better book for it:

"In February 2012 David Rathband is found dead in his home. A coroner says he deliberately hanged himself. You did that.

"In December 2013 a coroner holds an inquest into the death of Chris Brown. He died of shotgun wounds. You killed him."

Comments

Post a Comment