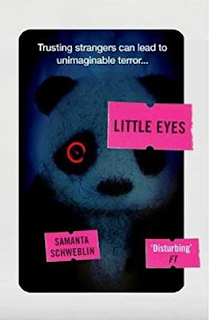

Little Eyes by Samanta Schweblin

We're all used to stories about artificial intelligence technologies and conflicts between AI and humans, and that's what I thought Little Eyes, the second novel by Argentine author Samanta Schweblin, would be. It imagines a craze for a new, relatively affordable product called a 'kentuki', effectively a small, furry robot animal with a camera, microphone and mobile connectivity to be kept like an artificial pet - but which soon begins to raise disturbing concerns.

However, this isn't a story about the dangers of artificial intelligence at all, because unlike electronic toys that 'learn' from interaction (remember Furbies?), every kentuki is actually operated entirely by an individual human being, randomly and anonymously connected to someone else's kentuki device via an app they've chosen to download.

That means the 'dweller' can not only control the kentuki's movements and behaviours, but also see and hear everything that goes on around it. If there's a language barrier between 'dweller' and 'keeper - and global connectivity means there often is - the app translates the keeper's words for the dweller. The dweller can't speak to the keeper, only make sounds, but customers soon find ways to circumvent this and communicate. Crucially, if the dweller disconnects from the kentuki, the kentuki becomes useless - it can't be reconnected to another dweller, and the previous dweller can't inhabit another one from the same device.

This short novel follows a selection of kentuki keepers and dwellers based in locations all over the world. A lonely woman in Peru, whose son has left home to live in Hong Kong, becomes fiercely protective of the young German woman she's now watching through the eyes of her bunny kentuki, particularly when she disapproves of her boorish boyfriend. Marvin, confined to his room to study by his father in Guatemala and desperate to see snow, finds a way to do so through the eyes of a kentuki in northern Norway. There's also Alina, living in Mexico with her inattentive artist boyfriend. Alina buys a crow kentuki out of sheer boredom, purely for the dopamine hit of unboxing something new, and then finds herself channelling her resentment and anger into torturing it, unaware of who its keeper might actually be and heedless of what she's exposing them to. Enzo, a divorced father in Italy, buys a mole kentuki for his son Luca, who actively dislikes it, but Enzo himself becomes so deeply attached that he's prepared to ignore a clear warning something badly wrong. Grigor, living in Serbia, sees a business opportunity in selling existing connections to new dwellers looking for something specific from their kentuki experience.

The cover of Little Eyes promises 'unimaginable terror', but that's a little misleading. The kentukis certainly bring out the worst in some of the people who keep and dwell in them, and that means there are some sinister and disturbing moments, but it's not as if we don't already know that people can be horrible, particularly when there's distance between them and their victim - think of people who abuse and threaten strangers online or groom children on social media. Any terrors in Little Eyes are human, and most of them very much imaginable. The book opens with a group of teenage girls bullying each other and being blackmailed by whomever their kentuki dweller: unpleasant, but unsurprising. Where things become more interesting is when becoming a keeper or dweller of a kentuki has a more unexpected effect.

Little Eyes is a fascinating exploration of the way humans use technology and how we form connections with people we've never met. I enjoyed reading about the different characters and the impact of kentukis on their lives and behaviour. But I think it falls down on a couple of elements.

Firstly, the potential motives for being a kentuki dweller, whether harmless or not, are obvious - through the eyes of the kentuki dwellers can see new places in far-flung countries, learn a new language, eavesdrop on conversations, pick up useful and potentially incriminating private information, or simply indulge a tendency to be nosy or voyeuristc.

But it's never actually explained why anyone would want to be a kentuki keeper. Kentukis don't talk or perform tasks or play games - all they can really do is trundle around watching and listening. The keeper has no power over when the kentuki is even active - and clearly, time differences would be an issue here. Moreover, everyone who owns a kentuki is fully aware that they are effectively letting an untraceable stranger into their home to spy on them and their family with absolutely no safeguards, and yet they continue to buy them - not only for themselves, but for their children.

We could certainly speculate about why this might be, but it's inexplicable that nobody really raises it in the novel. It would, in fact, probably be the most psychologically interesting element of the story. Little Eyes is a short book, not much more than novella-length, and its sparseness makes it both tense and accessible, but it also means that questions are unasked and consequences unexplored. It's those frustrations that make it a four-star read rather than a five-star one.

Comments

Post a Comment